As we prepare for our annual (give or take a pandemic) trek to India, we’ve been binging on movies and shows set around Mumbai and Delhi. Most of the action in the Australian TV series “Shantaram” takes place in our favorite Colaba neighborhood and in the slum around Geeta Nagar, both found on the southern Mumbai peninsula. One source of fascination has to be a comparison between how India and the United States approach the human urban flotsam we Americans call “homeless.” Such people bear the brunt of official and social slander and prejudice in both countries, but in India, they have in many cases organized and fought back to preserve what are in fact their homes. We’re not making a value judgment here—on the contrary, we’re wondering if fewer value judgments might make it easier for all of us to communicate and learn the lessons even these people have to offer.

Meanwhile…

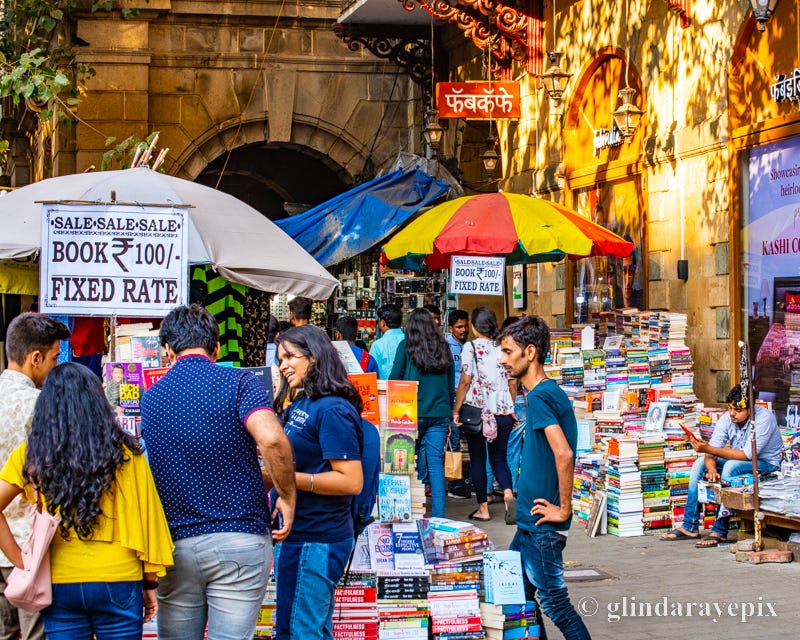

Friends once told us that the trick to visiting India is to go back a second time. We get what they meant. Our first trip was fascinating more than fun, too wrapped up in the culture shock for either of us to relax. In the Colaba District, we walked dozens of miles without really diving in, ate too much ho-hum Punjabi food because it was so easily available, and waded through all those massive crowds without really grasping what we were looking at. Don't misunderstand—we'd researched for months in advance and came away with a wonderful trip—just not a record-breaker.

Our second visit blew the doors off. We carved the stay into three phases—urban Mumbai, coastal Kerala, and the mountain tea plantations of Munnar—and emerged with three entirely distinct and thrilling experiences. Our only regret was that we flew across country instead of riding the fabled Indian railway system, but that just left more escapades for the future.

In Mumbai, where luxury hotels go for less than the cost of an American Holiday Inn, we splurged on the Taj Mahal Palace, one of the world's finest. They pick you up from the airport in a Jaguar limousine, check you in at the desk in your suite, and wait for your butler to come around to introduce himself. We're pretty sure many of the guests never leave the premises. Gin and Tonics in the garden, clothes made to order in time for dinner, rose petals strewn across your floor every night.

Outside the hotel gates lies an entirely different world, and yes, you do need to pay attention there. We usually arrive at New Year's, and so do more than a million celebrants from the Maharashtra countryside. At night, in the darker streets, colonnades, and arcades, you have to tread carefully, lest you trip over a sleeping family. During the day, those domestic tourists naturally want to take pictures with the most exotic sights in town—and often that happens to be you.

On a bus or a boat, in a crowded Muslim market or a Hindu slum, in a cinema or on a monument, people check quickly for your westerner's reaction. Long gone are the days when Memsahib could get away with a sniff of disdain or a whelp of disapproval. You're a guest in these parts, and the last thing anyone needs is your opinion on anything—even if they occasionally seem to be asking. When they don't find a hint of judgment in your features and body language, people go back to what they're doing and ignore you.

In the context of East-West cultural exchanges, three of our experiences might bear re-telling:

One morning on the crowded Sassoon Docks—which double as a key fishing depot and home for around 1,000 souls—we acquired a flock of children cheerfully demanding 10 rupee (roughly 13 cents). Indians give each other alms and expect Westerners to do the same, but these children were immaculate, and the begging was clearly more sport than necessity. We tried negotiating them down, but they were quite adamant about the 10 rupee figure. After we finally caved in, a few of them stayed with us, jabbering helpful hints and pointing out photo ops in Hindi, while politely pretending to understand our English replies.

Halfway through our walk, a Land-Rover appeared with a tour of American passengers we recognized from our hotel. In contrast to every Indian car we'd seen, they had their windows locked and hermetically sealed, and looked quite horrified at the depths of the Asian poverty they imagined they were experiencing. The rest of us found it both humorous and embarrassing, and we felt sorry for them. They reminded us of a man who once told us he'd never visit the third world because of the target indelibly printed on his American back. We couldn't have agreed more—in his case anyway.

From the Docks, we headed out onto the Colaba Causeway and got in line at a bus stop, planning to cross the city to the Haj Ali Mosque on the Arabian Sea. A passing taxi driver spotted us, screeched to a halt, and grew quite outraged when we turned down his cheapest fare. Mumbai taxi drivers can be a rude bunch, and no one in the uber-polite Indian crowd was surprised when we turned him away and climbed onto the rickety bus. But this was our first bus-ride, and we weren't prepared. The conductor demanded the fare, and we fumbled with a fistful of bills—something we never do in front of people—until a grumpy old gentleman told us to give the conductor 16 rupee. That was 21 cents for two crosstown fares.

And then, on our last day in Mumbai, we had three hours before heading out to the airport, so we went to a Colaba restaurant for lunch. On the way, a very sweet old woman heaved off a step and started a conversation. Like most Mumbaikars, she was plainly, but immaculately dressed, although she had an issue in one eye that was a bit disconcerting. She started out with general conversation, then insisted that her "son", a local tailor, could make us a shirt for almost nothing before we took off. We refused and went on to lunch, but when we came out, she was still working the street. Eventually, we let her take us to a local tailor, where they did indeed make us a beautiful custom linen shirt in two hours. She squatted in the entrance until we paid up—ridiculously cheap by American standards, outrageously expensive by Indian—and she received her commission.

The point being, that this was not a scam. It was just a different and very common way of doing business in the Third World. Yes, we overpaid, but there was no question about which among us needed the money more. On our next trip, if the Amah doesn't find us, we intend to seek her out—and complain bitterly, if politely, about her "son" overcharging us the last time. Along with the begging children, rude taxi drivers, impatient bus conductors, and bemused citizens, she plays a part in the vast pantomime called Mumbai. But you only get to play along if you open your metaphorical Land-Rover windows and let in the occasionally fresh air.