We were wandering through the Souk in Marrakech one afternoon, when an American tourist exited from a clothing shop, proudly showing off his new djellaba. The djellaba is a full-length, hooded and sleeved robe, worn by men since the dawn of North African civilization—except it's worn over long trousers and a sleeved and collared shirt, whereas this visitor wore his over underpants. His neck, chest, forearms, and ankles were bared for all the world to admire. His American friends were impressed with his daring launch into the culture. The passing Moroccans were aghast.

The subject of Arab and Muslim clothing never comes up in American conversation without someone opining on the subjugation of women in their Hijabs, Abayas, and Burkas. Yet, one glance will tell you that the men are just as constrained in their choices. You almost never spot any loud colors on anyone. Arms, necks, legs, and ankles are universally covered. Modesty, humility, and self-control are three great organizing principles of Arab public life (and on the rare occasions when they break down—as in riots, demonstrations, and wartime—you don't want to be anywhere nearby).

So we leave short sleeves, tank tops, shorts, and bikinis at home. In public, Glinda covers her head with a beautiful scarf or shawl. Ben wears a non-descript jacket over long, baggy, dark trousers, no matter how sweltering the day. We don't want to become the focus of anyone's conversation, because the truth is, as Christians and Westerners, we don't have a home here. And we don't mind, because we're not in Morocco to proselytize for our culture—we're here to learn about theirs. And as long as we respect these basic facts, the citizens, shopkeepers, and even officials are as correct, helpful, and even friendly as any people anywhere.

But why go anywhere we're not welcomed with open arms? Where our cash and touristy demands don't automatically propel us (at least in our narcissistic imaginations) to the front of the line?

For starters, these are the people who exploded out of the Arabian Peninsula in the seventh century to engage one society after another with one of the great muscular religions of history. That religion still comforts and informs the lives of almost 2 billion souls worldwide, and at a depth that is only a distant memory in many parts of the West.

And while it's easy for a skeptical Western elite to sneer at the devout—as Americans too often do at their own Southern faithful—religion gives a society cohesion. There is no more cohesive culture anywhere than in the Arab lands, and that alone makes them worth puzzling over. In-country, you're reminded of this five times a day, when the muezzin comes out of his minaret to summon the faithful to prayer.

And the land here is old in a way that is nearly incomprehensible for the children of a young society like America. The simplest of Berber traditions are rooted too far back in the mists of history to reliably record an origin. Some of the grandest civilizations have risen and fallen into the desert fossils, bleached and ground bones, and paving stones underneath your feet.

Poets and warriors, scientists and emperors, pirates and priests, have created, fought, trampled, and destroyed here. What you see around you is the complicated, uneven, and sometimes unfair legacy of those vanished millions.

Colonialism in these parts arrived in two distinct phases and flavors. In the first, the Muslim Moors, as they were then called, burst out of North Africa into Europe and swallowed up the entire Iberian Peninsula. The Spanish and later the French returned the favor, and when the inevitable exit came in Morocco, managed to disengage without the clumsiness of the French Algerian War next door.

So, be it invasion and mutual colonialism, an ancient history of wandering both ways, the long Atlantic Ocean littoral, simple proximity to Europe, or educational and commercial ties, Morocco has always been more outward-looking than its desert Arab cousins.

Nowhere is this connection more apparent than in the architecture. As in the Christian world, muslim religious authorities took charge of nurturing the earliest artistic traditions. The Qur'an's prohibition on the representation of idols, human or otherwise, gave rise to geometric, arabesque, and calligraphic patterns of infinite complexity.

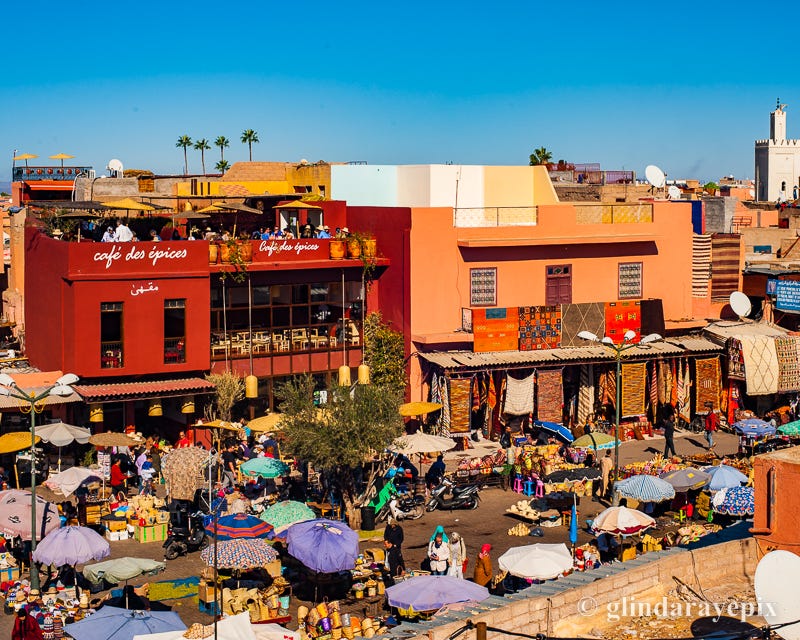

When you walk around the Medina and Kasbah of a Moroccan city, you will spot the ornate early glimmerings of the future Spanish architecture—until you file into a Mosque and find a vast, empty, contemplative space free of all those Christian saints and statues glaring down at your guilty conscience.

As in many European cities, the key historical influence on residential architecture was the tax collector, and the result can intimidate the visitor. Street lights are non-existent in the Souks and Kasbahs. Serpentine alleyways are fronted with drab, claustrophobic, mud walls that discourage official interest.

Yet open a door, and inside you’ll find an immaculate mini-palace with courtyards, fountains, elaborate living quarters, and ornate bedchambers. Such palaces, or Riyadhs, when converted into lodgings, are the only places we want to stay.

We are by no means done with traveling to Morocco. One bucket list has us taking a train from Paris down to Spanish Seville and then retracing in reverse the progress of the ancient Moors—a Spanish bus south to Algeciras, a quick ferry-hop across the Mediterranean to Spanish Ceuta, another bus to Moroccan Tangier, an overnight train south to Fez and Casablanca, and finally, a (preferably old and rickety) bus up into the Berber highlands of the Atlas Mountains.

Along the way, we’ll hopefully develop more of a taste for the cuisine. We didn't miss the bacon and pork chops from home, and it might just be us, but the celebrated local Tajine makes for a nicer kitchen ornament than a cooking implement. At least the way we've seen it, Moroccan cuisine lacks the angry kick of its neighbors in Tunisia and Algeria, much less the thrills and spills of the Lebanon and Istanbul.

But as we say, it might just be our Asian and Francophone tastes outing us. In food, as in everything else about the country, Morocco isn't a place you digest in one quick and easy—or rude and insensitive—bite. As Mama used to say, mind your manners and leave room for seconds and dessert.

I was In Morocco 25 years ago and still think about that trip. The highlight was driving through the Atlas with our guide, first stopping in Ouazazarte for lunch and then enroute to Zagora, we got a flat. Out of nowhere, and I mean nowhere, a little boy came running out with a pot of mint tea and three glasses. To this day I marvel at that.

Really like the way you give a deeper view of the places you visit. Makes me wonder why in india muslim women face more constraints than men when it comes to clothing.