One Parisian edifice you'll almost never hear mentioned by travelers (although it gives great photo op from the rear along Rue Mazarine) is the domed and resplendent Institut de France. This is odd, because this particular Left Bank bastion goes farther to explaining France, the French, and indeed the Parisians, than any other pile of ancient stones in town.

The Institut (in its Académie française) was founded in 1635 and has been run by some of the greatest thinkers in Western history—from Cardinal Richelieu and Voltaire to Victor Hugo and Raymond Poincaré, to Léopold Sédar Senghor. And from those medieval rumblings right up until today, the organization's primary focus has never wavered—namely, the preservation of the French language.

Think about that for a second. No other country boasts an official body responsible for the stability and purity of the words and syntax in which its citizens communicate.

We Anglophones go to the opposite extreme. When a President as clumsy as Warren Harding invents a word like "normalcy," politicians leap on board and insert it into every speech for the next hundred years. We communicate on the fly and entrust the precision of our language to unintelligible rock stars and the manglings of millennial cell phone users. To even suggest a desire for clarity or consistency gets the complainer labeled as some form of cultural supremacist—or worse.

But not in France. In France, no word enters the French language unless a committee of les Immortels (and yes, that's the official designation) approves it for inclusion in la Dictionnaire de l'Académie française. And not only are those words—that language—enshrined in the French Constitution, but every citizen is given not the duty, but the explicit right, to speak and use them in their everyday affairs.

Why does this matter?

Because it matters to the French you’re visiting. In spite of a flood of complaints about the Académie and its snail's pace in taking up new usages, no one in the mainstream is suggesting that it be abandoned. And yes, there are a gazillion revolts and regional variations, but the language of the Académie, the government, and the mass media—what you might call Parisian French—still reigns supreme.

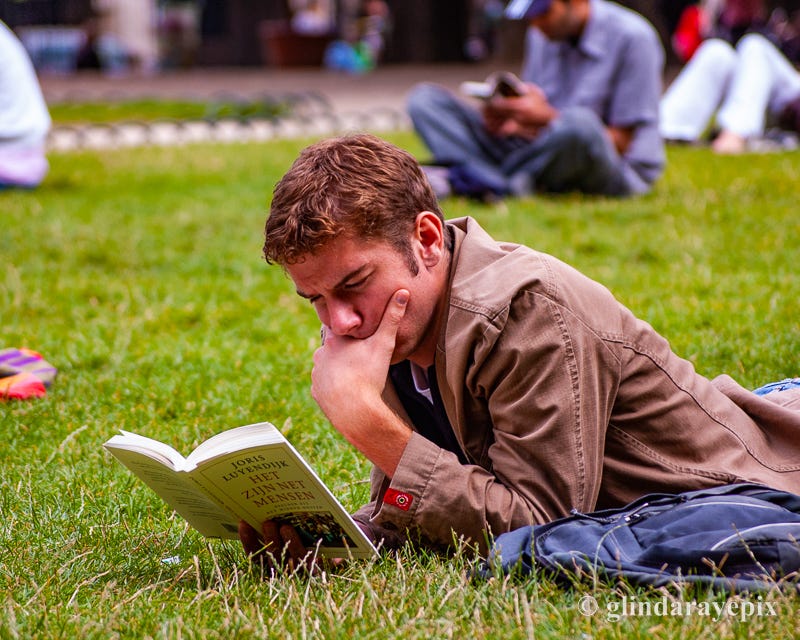

Nowhere does this show up more clearly than in Parisian café society. People who care about their words tend to care about their looks, their habits, and their conversation. So in a Parisian café, you might overhear elegant bickering over the latest Paris Saint-Germain soccer match, well-mannered critiques of the latest St. Honoré fashions, or a heated debate on the human condition and the origins of the universe.

To outsiders, in particular Americans, this all reeks (as maybe it should) of elitism and snobbery, but it also represents people taking their lives seriously. And the French, and in particular the Parisians, take everything about life very seriously.

Which makes it odd that, for most travelers, languages rarely make the pre-travel prep list. After decades of wandering around countries like Hungary, Turkey, Morocco, and India, we maintain a subscription at Rosetta Stone, but we're just as likely to open it to brush up on our French. There are several similar online apps—Duolingo comes to mind—that can at least get the traveler oriented.

Will anyone have a clue what you're trying to say? Probably not, but they'll respect you for trying. And in any culture, there's nothing like provoking a little gentle humor at your own expense to break the ice.

Several years ago, Ben was waiting outside a chocolate shop in downtown Paris, when a normally polite and elegant candy-buying Asian friend stormed out, empty-handed and furious.

"She refused to serve me!'

"She refused?"

"She didn't exactly refuse. But I was the only one in there, and she ignored me!"

"Did you ask her first if she spoke English? As in 'Bonjour. Parlez-vous Anglais?'"

"Why would I do that? Everybody speaks English here!"

And therein lay the issue. Ben took his friend's Euros and walked inside to a perfectly lovely reception from a perfectly lovely woman who spoke much better English than his French. And probably fluent German and Italian, and maybe even a little Russian too. But he didn't make the mistake of insulting her language.

And what a language French is—musical in its rhythms, soft in its intimacy, subtle in its worship of beauty, clever in its delight in the absurd, profound in its search for eternal truths.

Liberté! Egalité! Fraternité!

Or to quote Isadora Duncan's very last words, "Adieu, mes amis. Je vais à la gloire!"

No wonder the French love it so much.