We’re changing things up a bit on our Tuesday Odds & Ends missives for the next few weeks with a series of City Profiles—places as familiar as Houston or Barcelona and as distant as Istanbul or Mumbai. Like our Friday newsletters, these are going out free of charge to everyone on our mailing list. So if you’re not yet there, feel free to use the sign-up buttons below. There are no hidden obligations around these parts, and if we wax too dull and long-winded, you can always unsubscribe.

And a short note on spelling: Having grown up in Bruxelles, we use the French version of the city name. The local Dutch and Germans call it Brussel. The English, as is their habit, have mangled it into Brussels. We think someone somewhere still calls it Bruxelas, Bruselas, or Brosella. If you’re upset with the European Union, you’ll generally follow the Brexiteer lead in fulminating against a mythical hegemony known as Brussels. Not that anyone in Bruxelles seems to care.

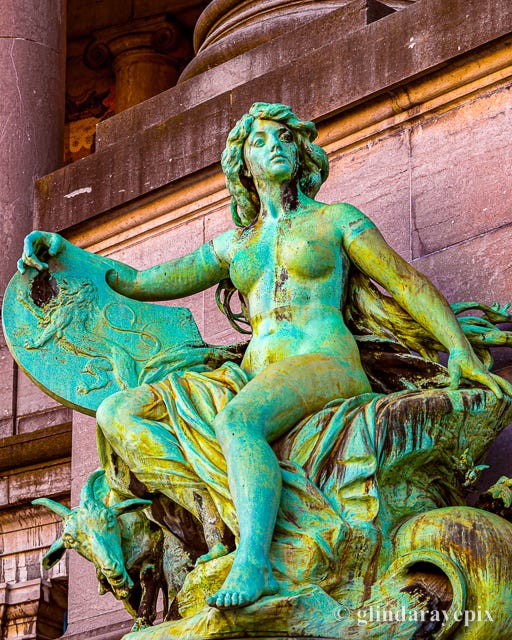

You can tell a lot about a country by sorting through its stock of public statuary:

Americans tend to favor—and then disfavor—resolute warriors, preferably seated on snorting steeds large enough to support a half-dozen selfie-snapping protesters.

Communist Russia replaced the smug Romanov boyars with angry, determined workers, then spread their stone-and-metal likenesses across eastern Europe like a kitsch factory on overdrive.

Italians can't resist a fondness for bold conquerors from a legend of two thousand years ago.

The French love myths of any kind, stolen or otherwise

The British vent their wind-blown imperial ambitions.

In Bruxelles, Belgium, the most celebrated statue—le Mannequin-Pis—is a two-foot-high fountain, first reported in 1451, of a three-year-old boy urinating into a canal.

Supposedly, his aristocratic father commissioned the artwork out of gratitude, after the son wandered off and was found relieving himself. Not that anyone really cares about the details. Every year, local mobs get drunk on the legendary Belgian brews and dress the bronze child in a gaudy, new outfit, without interfering with the free flow of his miniature stream.

Our own favorite gusher, le Cracheur (the Spitter), spews a constant stream of disdain from his wall perch between police headquarters and one of the oldest gay bars in Bruxelles. Here again, no one seems to care why he was sculpted (although his birthdate is fixed at 1704). Yet, when you consider that nearly all European fountains were built to supply water for drinking and washing…

Our next favorite icon, off the Grand' Place in Bruxelles, is a life-size brass wall inlay that commemorates the death of the obscure Brabantine patriot, Everard t'Serclaes. In 1356, Everard led a daring assault on the Flemings at the Bruxelles Hotel de Ville. Thirty years later, he was innocently walking down a peaceful street, when grudge-filled enemies recognized and cut him to pieces. It goes without saying, that the foreign guide books advise the gullible to rub Everard's arm for good luck (???).

But what do these statues all say?

In 50 BCE, when Julius Caesar was driving the Roman Empire northward through Europe, one of the few tribes he found nearly impossible to quell was the Belgae. These uncouth, illiterate savages did something no other tribe had managed, which was to turn the fearsome Roman Legions leftward toward the future British Isles.

Yet some areas of the globe are destined for invasion, and the tiny walnut-shaped wedge between France, the Netherlands, and Germany seems to be one of them. Over the centuries since the ancient Italians, the Belgians have reluctantly hosted Goths, Danes, Saxons, Austrians, Spanish, French, British, Dutch, Germans, and Americans.

Each invader has tried to shove its One True Religion down local throats, some with more success than others. All have left traces, making Belgium an authentic melting pot long before the first passengers set off for the New World. But none has entirely succeeded in breaking through the defining characteristic—the Thing about Bruxelles and Belgium—which is a healthy and persistent contempt for anything that represents official authority.

Rulers and rules be damned. The unit of social organization here isn't the state, the city, the neighborhood, nor even the street. The only structure that really matters in Belgium is the family.

In 2000, at the Millennium, the US Supreme Court decided a national election in part because no one trusted the country to go a day without a sitting government. In 2010, on the other hand, Belgium set a world record for surviving 541 days with no government at all. And hardly anyone noticed!

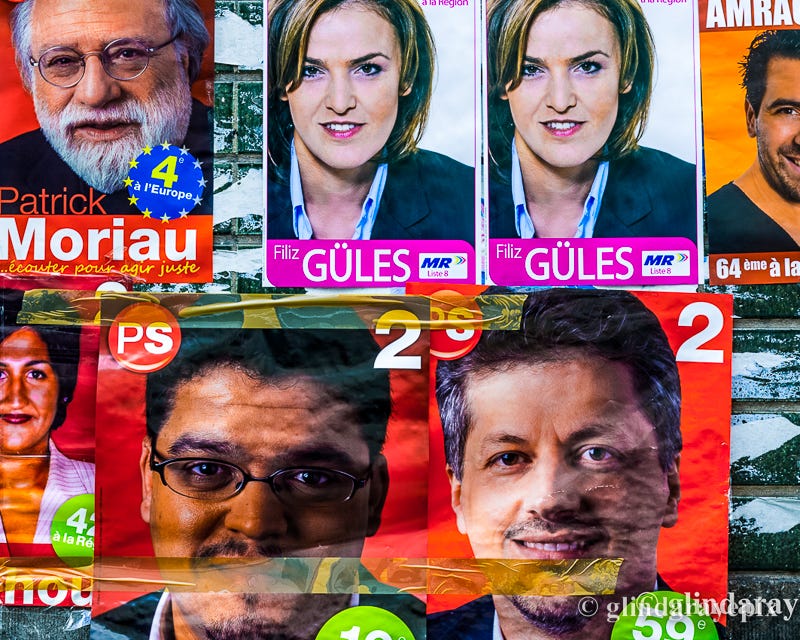

Belgian elections are lively, chaotic affairs, with three or four strands of political thought divided regionally into French, Flemish, and German versions. For a month or two, everyone gets excited, posters deface the walls, demonstrators fulminate, and the timorous US State Department issues an advisory. Then, just as quickly, the citizens get back to the business of living and ignoring city hall.

The longest-lasting and most successful invasion of this tiny country took place in 1831, not on the border, but in an obscure collection of London drawing rooms. By then, all the crowned heads of Europe had inter-married, rather than tainting their blood with the rest of us. So along with a hemophiliac gene and a British granny (Queen Victoria), the European royals shared the same irritable German uncle, Leopold von Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld.

If they all sported unearned crowns, why shouldn't he? Eventually, the mighty gave in and—while barely mentioning it to the locals—awarded the German-English-speaking-Protestant Leopold a French-Dutch-speaking-Catholic crown and the title Roi des Belges—King of the Belgians.

And this in turn led to a much more serious invasion, when Leopold's son—by then, King Leopold II—complained that he'd been left out of the race for imperial colonies in Africa. Once again, at the 1884 Berlin Conference, the European nations gave into Leopold II's grumbles and awarded him as a personal fiefdom the vast Congo River Basin.

This led to one of the bloodiest, most horrific scandals of colonial mismanagement in history—so bad, that ten years before the King died, obese and tired, in bed with his favorite Bruxelles prostitute, the frustrated Belgian government took away his prize.

The guilty secret, of course, is that the flood of money from the Congo turned Bruxelles into one of the most beautiful capitals in the world. The usual monuments and palaces are far less overbearing (and tourist-mobbed) than other European relics—after all, imperial pretensions only travel so far with a unruly populace that treats tax evasion like a second religion.

Yet Bruxelles sports the greenest park network of any capital on the planet, with gorgeous spaces ranging from the geometric Parc Royal and Grand Sablon to the sumptuous Botanical Gardens, to the leafy sprawls of le Bois de la Cambre and le Forêt de Soignes.

In 2016, when American journalists arrived in Bruxelles to cover the terrorist bombings at Zaventem Airport, they had a serious problem fitting Belgian chaos into their preconceived notions of how public life should work. They described the city as thoroughly misgoverned and segregated, and, much to our surprise, declared our own neighborhood of sixty years a "no-go zone for Caucasians” (???). Every time a protest breaks out, those same foreign newshounds fly in to quake, tremble, and misinform—even though their own footage might show bored café goers watching the excitement from the fringes.

The ancient name Brosella refers to the swamp along the Senne River with the evil air that has produced some of the finest lagers in the world. Today, the swamp might be filled in and driven underground, but the notion remains of dragging great things and great moments out of chaos, one puzzling, anarchic lunge at a time.

We're guessing this is the reason Bruxelles enjoys relatively few visitors, at least from the United States. Americans generally head to Paris and London for pretensions of aristocratic grandeur and to Amsterdam to misbehave amongst the tulips. In Bruxelles, you have a more subtle and polyglot reflection of the history and progress of Europe that has always caused its fans to crown it the Best-Kept Secret in Europe.

And like most locals not involved in the tourist trade, we don't mind if it stays that way.

Three mainline, but normally helpful websites for Bruxelles:

Haven’t been to Bruxelles in 40 years, this makes me want to visit again. I clearly remember having chocolate in the Grande Place (Vittamer?) and of course, who could forget the Mannequin Pis?! Enjoyed this, thank you.

Hello from America! Bruxelles has never really been on my travel radar, but now it is high on my list. I love your writing style by the way. Looking forward to your next post!